Who pays U.S. tariffs? Short answer: we all do.

A simple explainer for retailers and customers • As of August 12, 2025

Co-authors: Ellen Jacobson and ChatGPT (research & drafting assistance)

The short version

U.S. importers pay tariffs because they are the importer of record [1]. Payment is due at entry or via a monthly consolidated statement [3][4].

Those duties and tariff costs get rolled into the landed cost (total cost of goods from the factory to the port in the USA) and into the wholesale price and then into retail prices. Because sales tax is applied to the selling price, sales taxes rise when prices rise, too [10].

Overseas factories do not pay U.S. tariffs. They feel the impact indirectly via lower or delayed orders or pressure on FOB prices (their selling prices) (see current HTS/FR context) [5][6][7].

How we got here: lower-cost production abroad, higher-value work at home

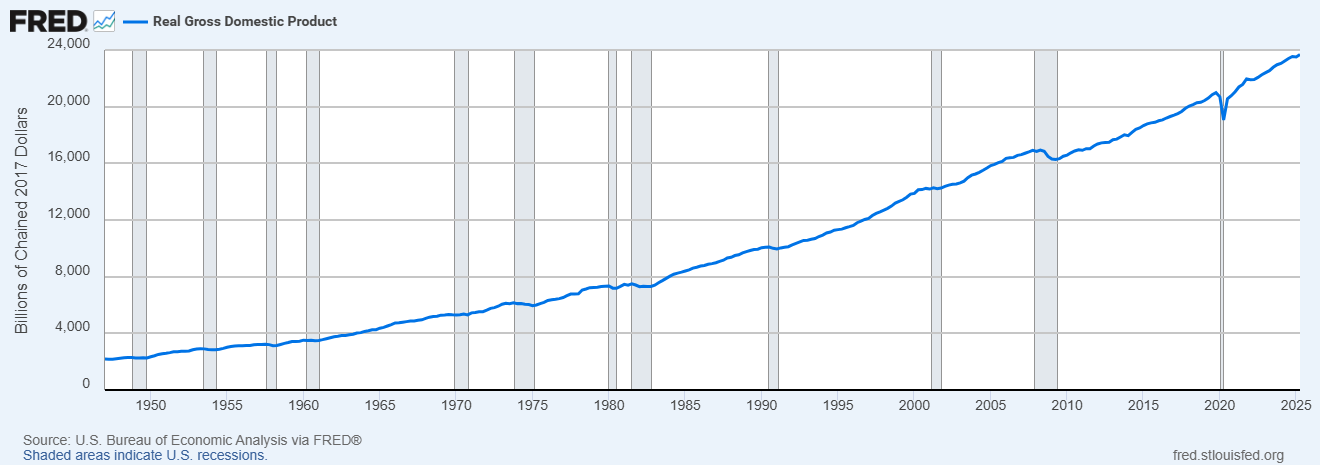

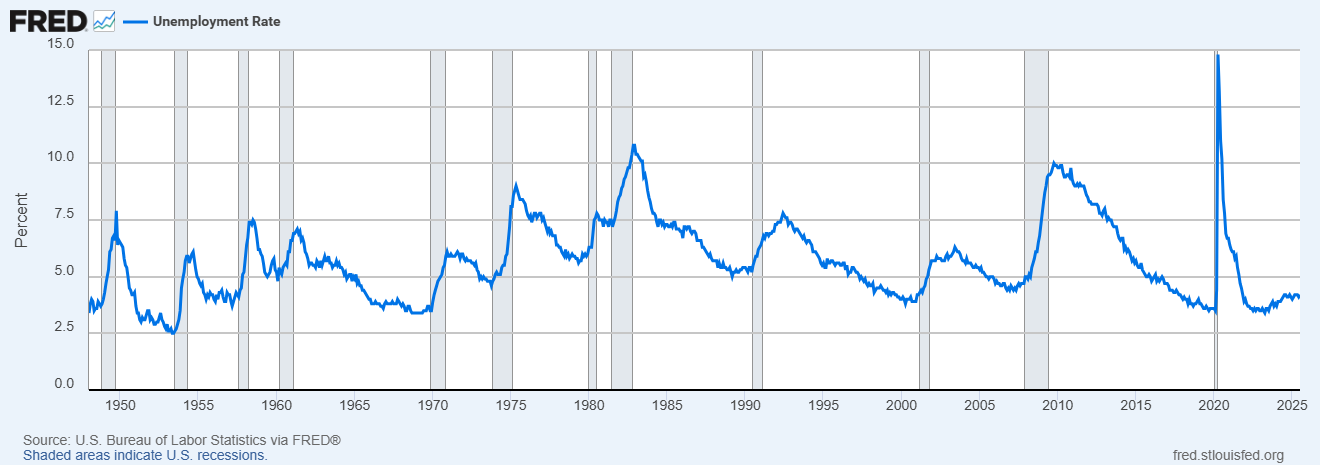

From the late 1980s onward, many labor-intensive goods (like apparel) shifted to lower-wage countries (for example, China and Sri Lanka) to keep unit costs competitive, i.e, low. At the same time, the U.S. economy specialized more in high-value activities such as design, marketing, software, logistics, healthcare, and advanced manufacturing. Result: a persistent goods trade deficit alongside a services surplus, with overall output growing over time. Proof point: Real U.S. GDP has climbed markedly over the past 50 years [8]. Unemployment has been relatively low in most expansions over that period [9].

Figure 1. Real GDP (GDPC1) — official FRED chart

GDP definition

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total market value of all final goods and services produced within a country’s borders over a specific period (usually a quarter or a year).

What drives U.S. GDP growth (quick hits)

Dynamic entrepreneurship and deep capital markets.

Strong universities/R&D pipeline and IP protection.

Openness to skilled immigration and global trade (access to large markets and inputs).

Periodic sector shifts (e.g., energy tech, IT, advanced services) that raise productivity.

Simply: GDP grows when more people work more efficiently with better tools, that’s why innovation, skills, investment, and participation matter.

Open live chart (UNRATE) on FRED

By the numbers: prices & COGS context

Long-run prices tell the story. Overall consumer prices rose roughly sixfold over ~50 years, while apparel prices rose far less, consistent with global sourcing and competition:

Consumer Price Index ” CPI” (All Items): prices up roughly 6× since the mid-1970s [11].

Consumer Price Index “CPI” (Apparel): up much less over the same period [12].

Figure 3. CPI — All Items (CPIAUCSL)

Open live chart (CPIAUCSL) on FRED

Figure 4. CPI — Apparel (CPIAPPNS)

Open live chart (CPIAPPNS) on FRED

Who writes the check (and when)

By law, the importer of record is liable for duties [1]. Importers file entry or summary and deposit estimated duties within about 10 working days of entry [3], or pay on a Periodic Monthly Statement if enrolled [4].

how the money actually moves (bond + ACH debit)

U.S. importers maintain a customs bond (usually a continuous bond) [2] and pay duties electronically through CBP’s (Customs and Border Protection) ACH system [3] — either within about 10 working days of entry or as one consolidated monthly debit under Periodic Monthly Statement [4]. The bond does not prepay duties; it guarantees payment and compliance. If an importer fails to pay, CBP can draw on the bond [2]. Either way, it’s our cash up front, which is why tariff costs flow into landed cost and, ultimately, into retail prices (and the sales-tax line, since sales tax is calculated on the final selling price) [10].

Illustrative landed-cost example (for context only)

Assume a bra (Tariff code HTS 6212.10, man-made), customs value (FOB) is $10.00. Base duty is about 16.9 percent ($1.69) [5]. If a 10 percent baseline tariff applies ($1.00) and a country add-on of 20 percent applies ($2.00) [6][7], total duties are about $4.69 (about 46.9 percent of customs value). The duty-paid customs value (total of COGS & Duties) is therefore $14.69 ($10.00 + $4.69).

Note: The $14.69 figure does not include international freight, drayage, inland freight, warehousing, pick and pack, insurance, customs brokerage fees, MPF/HMF, financing or bank fees, administrative overhead, sales commissions, research and development, marketing, or taxes. These direct and indirect costs also affect the final shelf price and, in turn, the sales-tax amount since sales tax is calculated on the final selling price [10].

What to tell customers

Tariffs are U.S. taxes collected at the border from U.S. companies. We pay them up front to bring goods in [1][3][4].

Those costs increase our landed cost before expenses, which usually means higher retail prices and higher sales tax because it’s calculated on the final selling price [10].

We continually work on sourcing and efficiencies to soften increases, but the current tariff structure on many origins is significant [5][6].

Tariffs affect price, but the right fit saves money over time. Start with our quick Fit Guide, then see the best sellers built to last.